Historic Hamilton Canal connects Negombo to its many-layered past

The Hamilton Canal waterway that threads through the heart of Negombo feels timeless, yet its story is a mirror of Sri Lanka’s layered past.

Today known as the Hamilton Canal—or locally as the Dutch Canal—this 14.5 km ribbon of water links the Puttalam coast with Colombo, passing the heart of Negombo and tracing centuries of trade, engineering and environmental experiment.

Canal-building along Sri Lanka’s western seaboard goes back long before Europeans. Kings of the Kotte kingdom had earthen channels and sluices cut to connect villages and lagoons so spices, rice and cinnamon could move to ports.

The Portuguese and later the Dutch expanded and formalised these waterways in the 17th and 18th centuries—both to move goods and to try to manage the tricky tidal saltwater that flooded low-lying marshes. The Dutch-era network became known broadly as the Dutch Canal.

When the British took control at the turn of the 19th century they set about completing and realigning stretches of the system.

Between 1802 and 1804 the canal we now call Hamilton was dug or improved under British direction and named after Gavin Hamilton, the Government Agent of Revenue and Commerce.

It ran closer to the sea than some of the older Dutch channels and was intended principally to drain saline water from the Muthurajawela marshes and to facilitate barge transport. Ironically, the interventions altered tidal dynamics and in places increased salinity rather than relieved it.

Transport

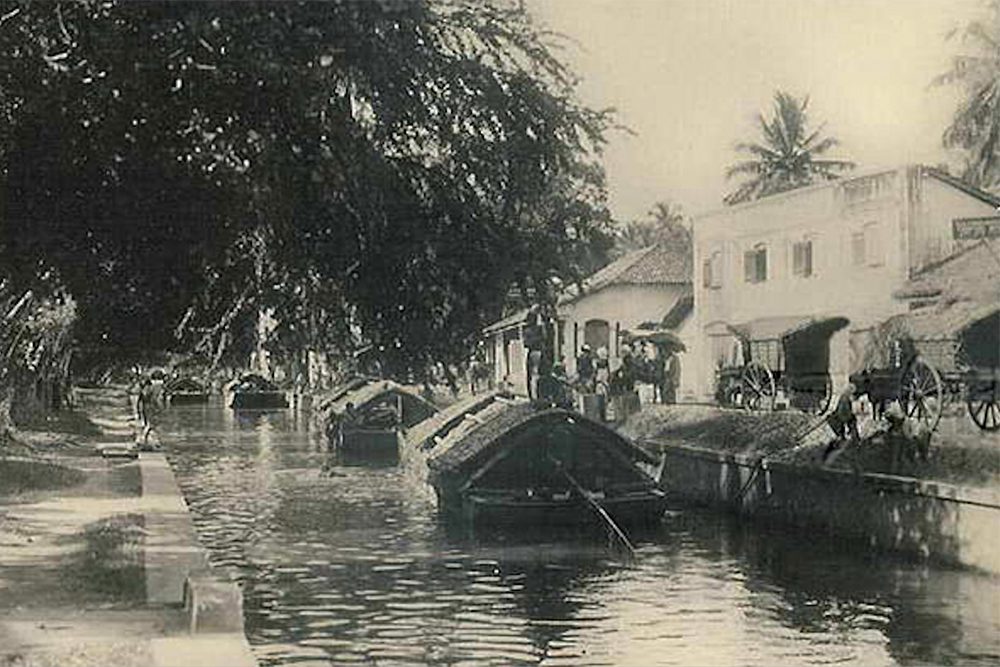

Through the 19th and early 20th centuries the canal was a working transport artery—boats, padda craft and barges threaded its length carrying cinnamon, produce and, later, local commuters—until the arrival of rail and road reduced its freight role and parts of the channel fell into neglect.

Through the 19th and early 20th centuries the canal was a working transport artery—boats, padda craft and barges threaded its length carrying cinnamon, produce and, later, local commuters—until the arrival of rail and road reduced its freight role and parts of the channel fell into neglect.

In recent decades the Hamilton Canal has enjoyed renewed interest: restoration and clean-up programmes, small boat tours and local conservation efforts have revived stretches of the waterway as a cultural and eco-tourism resource, offering quiet boat rides past fishermen, colonial-era walls and palms.

Today the canal is best experienced slowly—on foot from one of Negombo’s small bridges or in a low boat at sunset.

It’s an urban seam where tidal forces, colonial ambition and local livelihoods still meet: a human-made landscape that keeps telling the same practical, layered story—of trade, drainage, miscalculation and, now, gentle recovery.